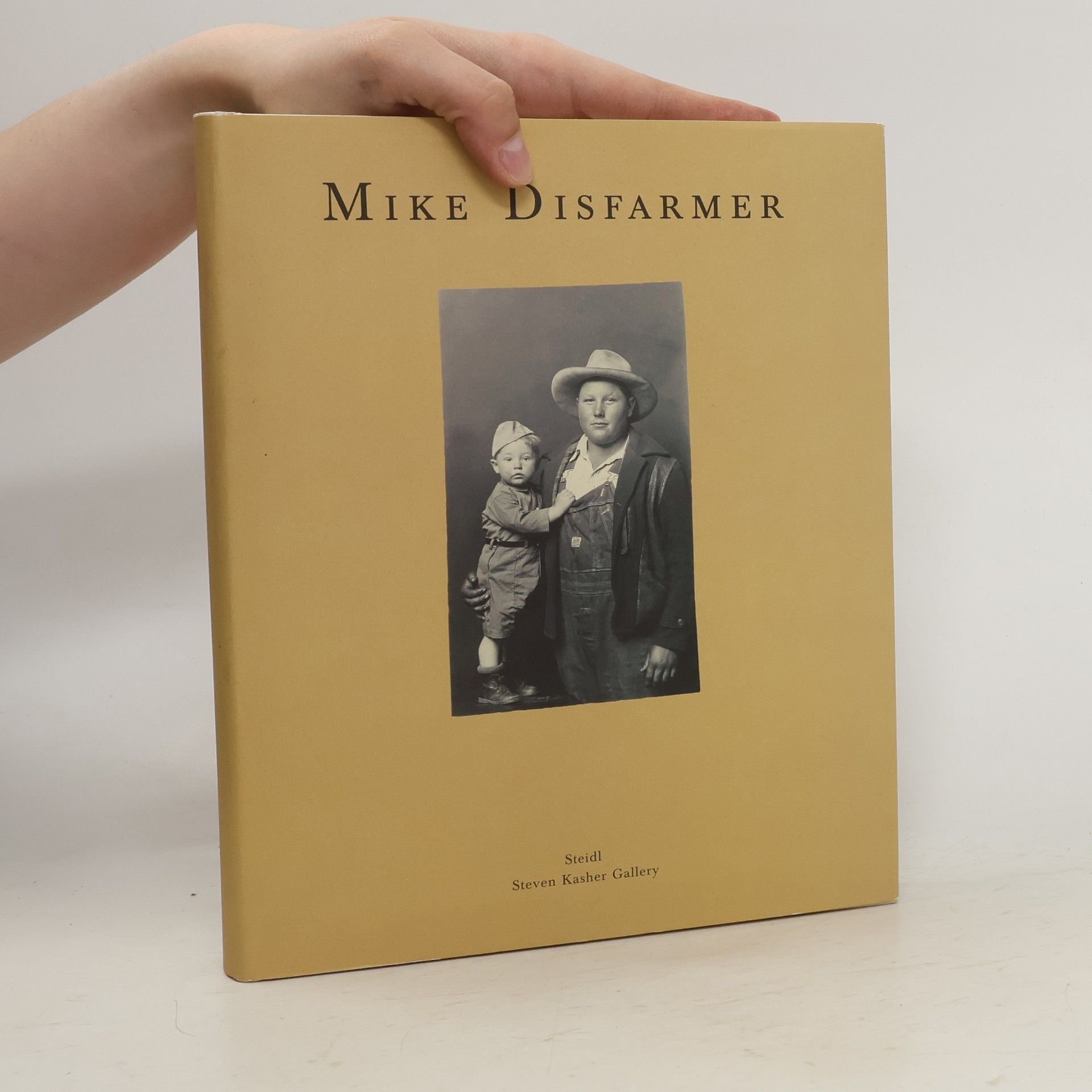

Last year, as The New York Times has reported, a young couple from Heber Springs, Arkansas offered a collector 50 family photographs, unassuming black-and-white studio portraits dating from the mid-twentieth century. That quiet sale, which raised the possibility that there were other vintage prints of Mike Disfarmer's work in area family albums, set off a competitive buying frenzy that had collectors going door to door through rural Arkansas, spending more than a million dollars on several thousand prints. Disfarmer's work had originally been discovered in crates of glass-plate negatives, found by the speculator who purchased his estate. It was brought to light decades later in a series of books and exhibitions that set off consistent, continuing critical acclaim, but known only in posthumous reprints. Original Disfarmer Photographs is the first publication to present these vintage prints, made by Disfarmer's own hand at the time the pictures were taken--at once family mementos and the original work of one of America's greatest portraitists. Disfarmer spent half a century making studio portraits at pennies a picture to satisfy his rural clients, and creating a style of portraiture all his own. As one subject describes its genesis, "There wasn't much of a greeting when you walked in, I'll tell you that. Instead of telling you to smile, he just took the picture. No cheese or anything."

Steven Kasher Knihy