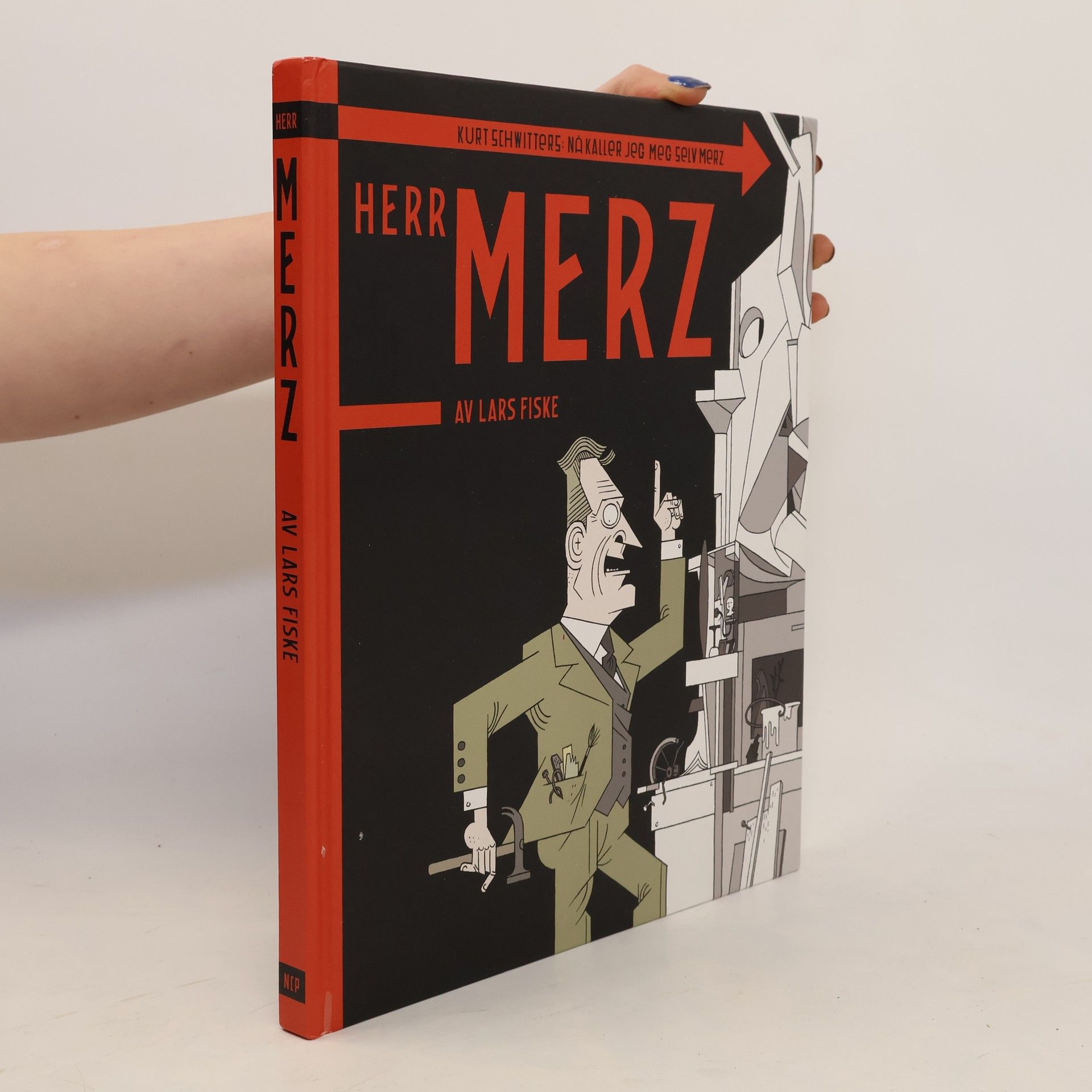

Herr Merz

- 116 stránek

- 5 hodin čtení

En tegnet biografi om den tyske dadakunstneren Kurt Schwitters av Lars Fiske. I 1919 startet Kurt Schwitters (1887-1948) sin egen dadaistiske kunstretning Merz i sin hjemby Hannover og ble en av de store pionerene innen modernismen. Schwitters hadde omgang med tidens store avantgardekunstnere og var selv aktiv innen alle kunstuttrykk. Hans totalkunstverk Merzbau, verdens kanskje aller første installasjon, var langt forut for sin tid og sammen med lyddiktet Ursonaten sjokkerte Schwitters både besteborgere og dadaister og satte sin kunst på kartet for evig tid.På slutten av 20-tallet forelsket Schwitters seg i Norge og vestlandet og tilbrakte hver sommer her i landet på 30-tallet. Da nazistene tok makten i Tyskland ble hans kunst stemplet som degenerert og i 1937 gikk Schwitters i eksil i Norge. Historien om årene i Norge er et av tyngepunktene i Herr Merz.Herr Merz er en utvidet og omarbeidet utgave av Schwitters-biografien som ble publisert i Steffen Kverneland og Lars Fiskes kritikerroste og flerfoldig prisbelønte samarbeidsprosjekt Kanon. Med Herr Merz fullfører Fiske med grensesprengende fortellerteknikk sitt grafiske nybrottsarbeid i en stor og vakker bokutgave.